[Lateral Ankle Sprains.]

You’ve just sprained your ankle while at practice, and are probably wondering what your next steps are. ‘How bad is it? How long will I be out? What should I do about it? Should I tape it?’

In the National Athletic Trainers’ Association Position Statement on Conservative Management and Prevention of Ankle Sprains in  Athletes, research shows that “In sport, ankle injuries are the most common injury, with some estimates attributing upward of 45% of all athletic injuries to ankle sprains.” 1

Athletes, research shows that “In sport, ankle injuries are the most common injury, with some estimates attributing upward of 45% of all athletic injuries to ankle sprains.” 1

The position statement also mentions that individuals who sustain initial ankle sprains are at higher risk for re-injury, can experience prolonged symptoms, are predisposed to develop chronic ankle instability, and may have an increased risk for ankle osteoarthritis. 1

To most, these statistics and outcomes can come across as bleak, and not very promising. However, with our knowledge of the human body and understanding of the physiology behind healing developing more as time goes on, we have a better grasp on what factors can improve recovery outcomes.

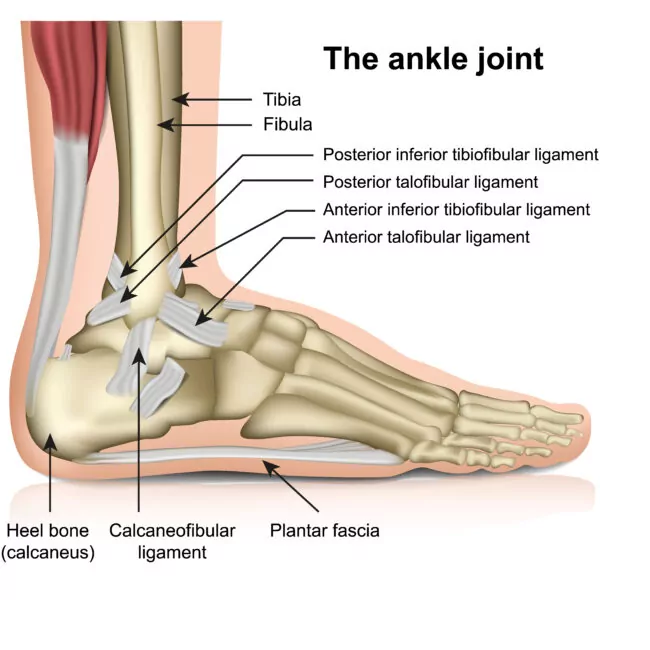

Before discussing the rehab protocol and return to sport after ankle sprains, it is imperative to understand some basic anatomy of  the joint. The lateral aspect (or outside area) of the ankle consists of three main ligaments that support the joint. When ankle injuries occur, one ligament in particular, the anterior talofibular ligament, is most vulnerable to injury.2 This ligament is commonly subjected to injury when the mechanism of rapid inversion and internal rotation (foot rolling inwards) of the foot occurs while the joint is being loaded.3

the joint. The lateral aspect (or outside area) of the ankle consists of three main ligaments that support the joint. When ankle injuries occur, one ligament in particular, the anterior talofibular ligament, is most vulnerable to injury.2 This ligament is commonly subjected to injury when the mechanism of rapid inversion and internal rotation (foot rolling inwards) of the foot occurs while the joint is being loaded.3

The extent of structural damage to the ligament is a substantial factor in estimating recovery time. Ankle sprains can range from mild discomfort and localized swelling, to ligament elongation and partial tearing, to full ligament rupture. When the anterior talofibular ligament is injured to the point of structural breakdown, there is an automatic failure in the joint support system.5 Timeframes for injury healing can range from as little as 3 weeks, to anywhere from a few months to a full year. While this is indeed a wide range, average lateral ankle sprain recovery times tend to fall within 4-6 weeks. 5, 6 Based on research, we know that there is evidence out there that shows signs of anterior talofibular ligament healing after 6 weeks. This evidence is backed by typical wound healing stages, with proliferation (new tissue formation) occurring within 4-8 weeks of tissue repair.6

When considering rehab for lateral ankle sprains, there are a few domains to be considered. These include range of motion/mobility, strength, proprioception/balance, and sport specific movements. During the initial rehab phase, reducing swelling and gaining back range of motion is the first priority. This is followed up by strengthening the surrounding muscles, then integrating exercises to increase proprioception and work back into sport specific movements. All phases considered, the full rehab protocol can take anywhere from a few weeks to a full year to fully return to sport. Return to sport will depend on whether the ankle joint has full range of motion, strength, and if it can handle functional movements required for the intended sport.

When progressing back into sport specific activities, research has shown nominal evidence supporting the use of ankle braces, or ankle tape initially to reduce recurrent ankle sprains.1,7 However, the extent to which these supporting devices work to reduce the risk of recurrent ankle sprains is inconclusive and requires more research. Still, bracing or taping is typically recommended for the first phase of returning to sport.7 Once the return to sport is complete and the ankle is able to handle full functional movements without fail, it is recommended a maintenance rehab program be implemented. Continuing to strengthen the ankle and improve proprioception will play a role in reducing recurrent ankle sprains in the future.

Ask one of our athletic trainers to provide you with an ankle rehab program to do at home or at the gym! It’s always better to try and prevent injuries in the first place than trying to play catch-up after an injury occurs.

RESOURCES

- Kaminski TW, Needle AR, Delahunt E. Prevention of Lateral Ankle Sprains. J Athl Train. 2019 Jun;54(6):650-661. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-487-17. Epub 2019 May 22. PMID: 31116041; PMCID: PMC6602401.

- Kumai T, Takakura Y, Rufai A, Milz S, Benjamin M. The functional anatomy of the human anterior talofibular ligament in relation to ankle sprains. J Anat. 2002 May;200(5):457-65. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00050.x. PMID: 12090392; PMCID: PMC1570702.

- Delahunt E, Bleakley CM, Bossard DS, Caulfield BM, Docherty CL, Doherty C, Fourchet F, Fong DT, Hertel J, Hiller CE, Kaminski TW, McKeon PO, Refshauge KM, Remus A, Verhagen E, Vicenzino BT, Wikstrom EA, Gribble PA. Clinical assessment of acute lateral ankle sprain injuries (ROAST): 2019 consensus statement and recommendations of the International Ankle Consortium. Br J Sports Med. 2018 Oct;52(20):1304-1310. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098885. Epub 2018 Jun 9. PMID: 29886432.

- Hubbard TJ, Hicks-Little CA. Ankle ligament healing after an acute ankle sprain: an evidence-based approach. J Athl Train. 2008 Sep-Oct;43(5):523-9. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.523. PMID: 18833315; PMCID: PMC2547872.

- Chen RP, Wang QH, Li MY, Su XF, Wang DY, Liu XH, Li ZL. Progress in diagnosis and treatment of acute injury to the anterior talofibular ligament. World J Clin Cases. 2023 May 26;11(15):3395-3407. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i15.3395. PMID: 37383912; PMCID: PMC10294195.

- Mansur H, Durigan JLQ, Contessoto S, Maranho DA, Nogueira-Barbosa MH. Evaluation of the Healing Status of Lateral Ankle Ligaments 6 Weeks After an Acute Ankle Sprain. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2024 Nov-Dec;63(6):637-645. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2024.07.004. Epub 2024 Jul 25. PMID: 39067610.

- Vuurberg G, Hoorntje A, Wink LM, et alDiagnosis, treatment and prevention of ankle sprains: update of an evidence-based clinical guidelineBritish Journal of Sports Medicine 2018;52:956.